Making Utopia (performance)

30-08-2022

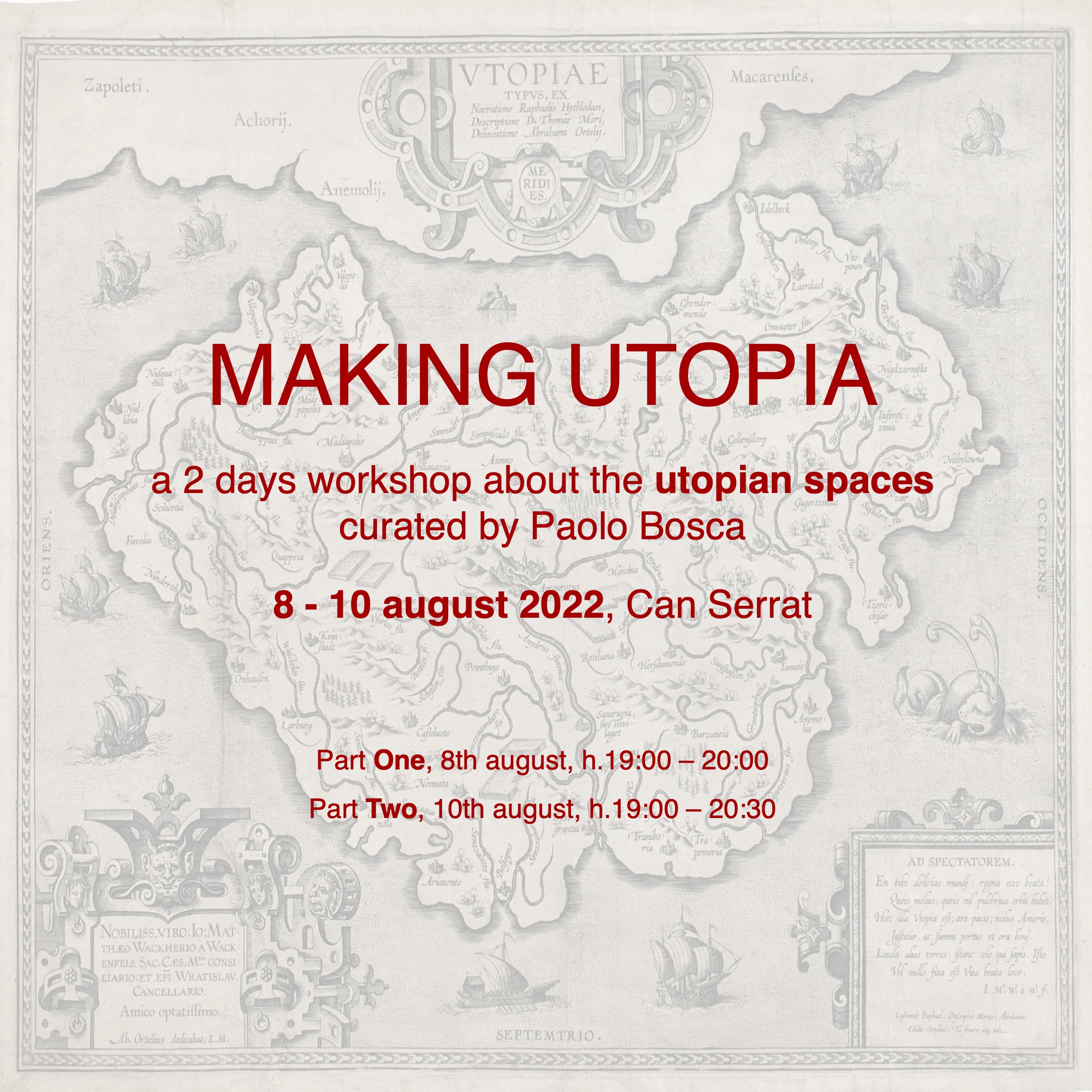

Making Utopia is a workshop I organized at the Can Serrat residency in Spain to reflect on how utopia can become part of the inhabited space and the concrete space of imagination.

The first step was to hand participants an introductory text, which can be found below. Then there was a collective moment of discussion in which I asked everyone to write a “utopian act,” a concrete, feasible action, but considered utopian. Once all the sentences were written, we discussed the various meanings of utopia that could be drawn from the sentences written by the participants. It was a valuable opportunity to re-discuss the preconceptions we all have about this word at once unreachable and deeply intimate. Fears, frustrated desires, and limits imposed and never fully internalized were discussed. Through discussion we also began to think about how to realize our utopias.

Two days later everyone brought their own way of realizing utopia, and the results were amazing. It was amazing how an island, or rather, an archipelago of small islands was truly created where a real temporary utopia was going on from time to time, where it was possible to talk openly about one’s fears, to change one’s point of view on daily life for a few minutes, to forget a too- pressing historical context, to have the freedom to climb a ladder and descend only when one is happiest.

MAKING UTOPIA (full text)

Utopia is an elusive concept. We are used to think that it is part of the future, in the form of a project or an ideal, and when the future turns into a dark and inhospitable place due to the devastating processes that are taking place both naturally and socially, then the utopia that inhabits that future is overturned and becomes dystopia.

Fortunately, utopia does not exist, nor can exist, indeed, it is such precisely by virtue of the fact that each of its shots is, after all, just shooting blanks. We cannot say the same about dystopia: who tells us that it cannot exist, and who tells us that it is not already here somewhere?

Utopia is not born in time, but in space. Utopia is also “somewhere”, only to reach it there are no maps, on the contrary, you have to get lost. The name comes from a book written in the XVII century by Thomas More, in which the author reports the words of his friend Raffaele Itlodeo, who has just returned from Utopia. Like this first historical occurrence, all the first utopias that subsequently appeared also have some spatial characteristics in common: they are all islands and, to reach them, one must get lost. There is no map that indicates the way to Utopia.

After all, the word itself is more about space than time. Today this neologism has a mainly political meaning, but it is important to remember that it carries spatial meanings with it. Topos, U (non) - Topia (placeness), means place in ancient Greek. Utopia is therefore a non-place also in the sense of a place that cannot be reached through the traditional notions of space and, above all, through the tools we have to interpret our position in space, first of all the map.

In this sense, utopia is an act more than a project: it is the act of leaving the traditional space (in which many of the power structures are located, such as borders) to reach a space which is “other”, free, in which things can be real that otherwise could not exist.

For these reasons utopia exists, utopia is something to make. But how?

Let me give some examples: Stalker. Nomadic Observatory, is a group of Italian artists who use the walk as an artistic practice, in order to create journeys and ephemeral spaces of freedom that are realized only for a certain period of time during - and thanks to - the path and then disappear. Walk in a circle on a lawn, crushing the grass, to create an area that will remain visible only for a few hours, or walk the shadow that a large building projects on the grass behind it; are some of the actions that this group has taken over the years to make manifest the impact of power on space and to try to build, in the same space, areas of disobedience that cannot be delimited by power itself. James Scott is an American anthropologist who has dedicated part of his studies to an area of Southeast Asia that has always escaped State domination. To identify it it’s necessary to pay attention to common practices, shared by the inhabitants of various highlands located between the national borders of Sri Lanka, China, Vietnam and other neighboring countries, which draw an area recognizable at an anthropological level but elusive by the control tools of the space used by State. The same is true for nomadic peoples, for example the Rom, who retain their own identity and presence in the space of the world, which however is expressed in ways that are completely opposite to those with which the political system is positioned on and in space.

A moving shadow, a nomadic people, a highland population, a circle drawn in the grass: these are all examples of utopias in space. Each of them has a political value and strength, as we are used to think, but none express itself as a future project. They are expressed through acts contemporary to us. Utopia is already here, too; just make it.